As the world suffers a nonstop series of calamities, the effort to look for life beyond Earth may seem frivolous. The reaction of some will be to say “yes, that’s a nice thing to do, but not an important thing.”

This presumption is myopic because of the weighty societal implications of the activity we call exploration.

Hunting for extraterrestrial biology differs from most science in that its hypothesis can’t be disproven. Most researchers think there must be life elsewhere in the cosmos, and polls show that the public generally agrees. But unlike the majority of research assertions, there’s no way to demonstrate that such life doesn’t exist. The hypothesis of a universe laced by biology can’t be falsified.

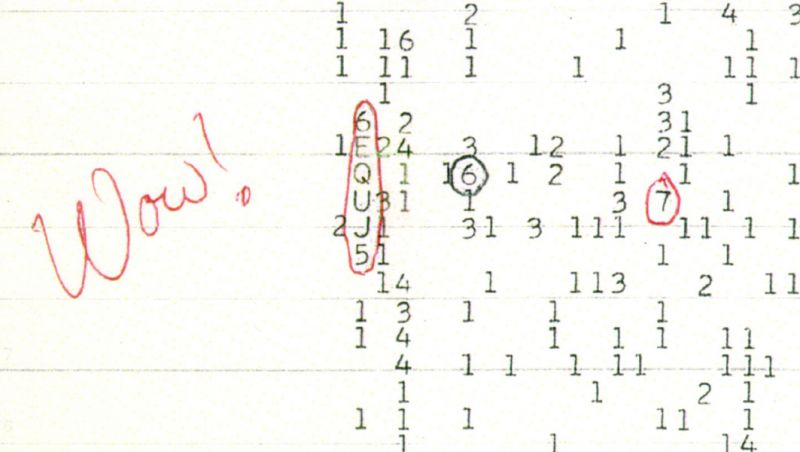

So, by the conventions of science, you could say that our experiments to find other life – whether microbes in the Solar System or extraterrestrials on a planet hundreds of light-years away – are not really experiments: they’re searches. They’re exploration.

As a social activity, exploration has been essential to survival. The ancient Egyptians weren’t terribly interested in lands beyond the shores of the Nile, leading to ossification of their culture and its eventual subjugation by the Greeks and the Romans. The Renaissance, which marked the transition from feudalism to modernity, might have stalled if it hadn’t been accompanied by the Age of Discovery.

Exploration is deeply consequential.

But let’s be honest: It’s not always selfless. James Cook, one of history’s greatest navigators, wasn’t commissioned for a slow-speed ride into the Pacific just for the heck of it. The English admiralty had specific goals, mostly rooted in money. They tasked Cook with finding Terra Australis and later the Northwest Passage, objectives that were driven by the possibility of trade.

Admittedly, it wasn’t entirely about the almighty pound. In Tahiti, Cook made astronomical measurements of the transit of Venus, an experiment designed to calibrate the scale of the Solar System. So yes, exploration can be pursued simply to expand our knowledge, even if such noble sentiments are frequently alloyed with matters of practicality, greed, or a bid for national pride.

But here’s the question: Even though it was possible to convince the citizenry of 18th century England that funding Cook’s leaky ship was worth the tax money because, ultimately, it would literally enrich them, how marketable is searching the cosmos for life? Doing so will have no benefits in terms of trade, raw materials, claiming new lands, or establishing colonies. It will do none of that.

But there are other justifications.

For example, there’s the matter of simple curiosity – a seemingly lightweight word. But curiosity has led to good things: clever inventions and major revelations in natural science, psychology, medicine, social behavior, and just about everything else. Curiosity is too easily dismissed.

You might also argue that finding extraterrestrial biology will give us cosmic context; we’ll have insight into our own importance. Imagine if the Aztecs of 1400 had been informed that there were large cities on the other side of the oceans. Would that not have affected them in some profound way? People have suggested that finding intelligent beings on distant planets would be good news for us, demonstrating that Homo sapiens is not inevitably fated to self-destruction. If the aliens can survive their own technology, so can we.

These arguments make for pleasant lunchtime chatter. But trying to defend our profound interest in exploration this way is to sidestep the fact that evolution has built into our natures our wish to learn something new. And sure, you could point out that there’s obvious survival value in wanting to know what lies beyond the nearest chain of hills. But the fact that such interest is hard-wired into our primate brains shouldn’t cheapen its value, any more than finding an evolutionary explanation for music somehow makes it less worthwhile.

Exploration has always been important, and its practical spin-offs are often the least of it. None of the objectives set by the English Admiralty for Cook’s voyages was met. And yes, the exploration of the Pacific often left behind death, disease and disruption. But two-and-a-half centuries later, Cook’s reconnaisance still has the power to stir our imagination. We thrill to the possibility of learning something marvelous, something that no previous generation knew.

It is this quest to understand and to know that drives our exploration of other worlds. To view its pursuit as a superficial entertainment and a shallow diversion is to ignore something deep in our makeup. It is among the best things that our species does.