The Story of Astronomers and Citizen Astronomers Catching Hazardous Apophis Asteroid over Colorado and Louisiana

Franck Marchis, Chief Scientific Officer of Unistellar and Senior Planetary Astronomer at the SETI Institute, tells us the whole story, from the first hint to the latest revalations about this unique citizen scientist planetary defense campaign.

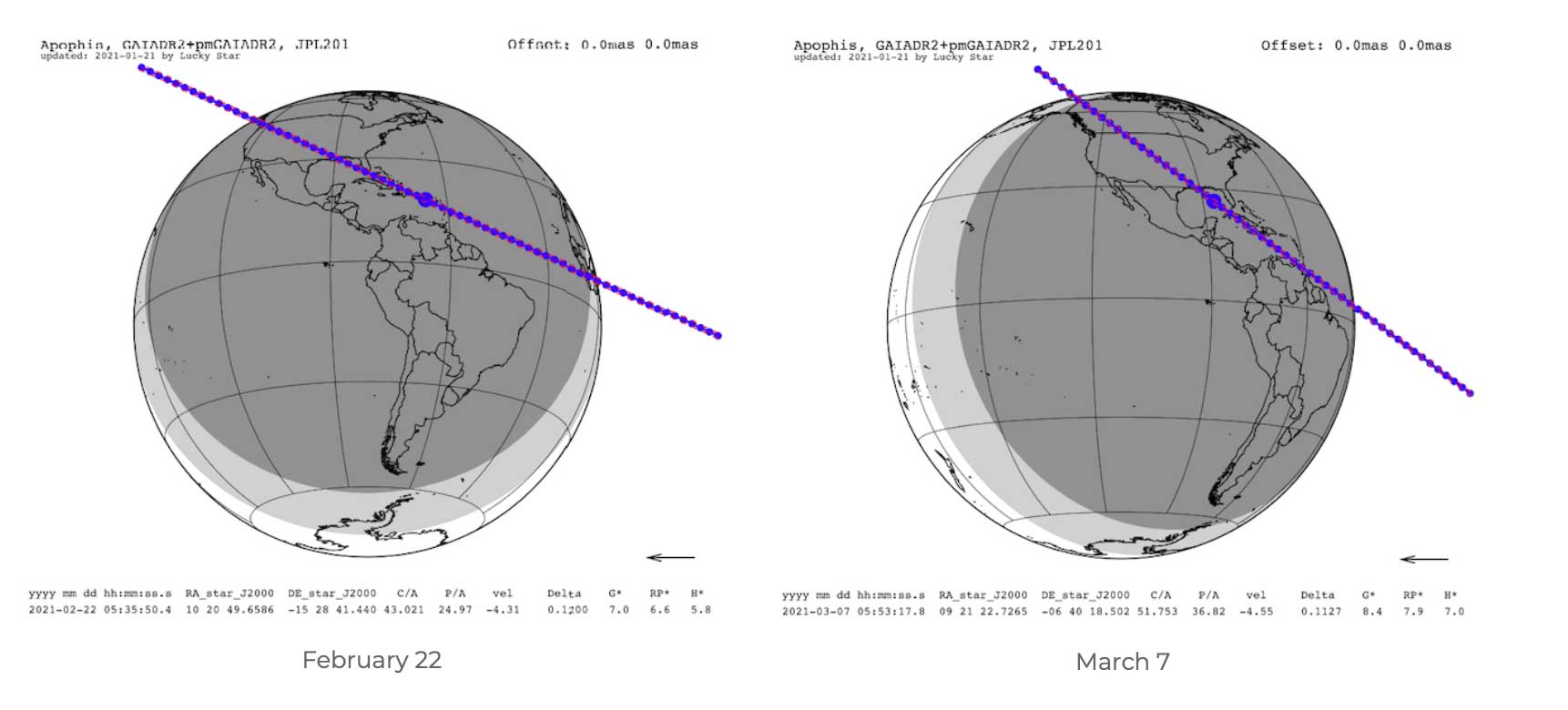

Like most things in science, it started with an email. On February 1, 2021, Josselin Desmars, from the Observatoire de Paris, contacted me to say that he had used his model to see if potentially hazardous asteroid (99942) Apophis would occult bright stars during its upcoming close approach to Earth and found two interesting events: one on February 22, 2021, and the other on March 7, 2021. During both events, the asteroid’s path would cross the United States along almost the same thin line from Montana to Louisiana.

Why this sudden interest in Apophis? There are about one million asteroids in the Solar System, 20,000 of which are near-Earth objects. Apophis, which was discovered in 2004 by Roy Tucker, David Tholen, and Fabrizio Bernardi, is an Aten asteroid that’s about 370 m wide and comes close to Earth every decade or so. It is usually considered as one of the most potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroids of the next decades.

Recent observations taken with the ESA space telescope Gaia surprised astronomer David Tholen: it showed that the object’s orbit is accelerated because it interacts with the Sun. This means that the asteroid’s orbit is not well-established—not what we want to hear for something that has a 1-in-150,000 chance of crashing into Earth in 2068.

Josselin and I quickly confirmed that a detection of Apophis during those stellar occultations would give us a very accurate fix on its location (i.e., accurate to 0.2 km) and refine the orbit significantly. So, on February 10th, we opened a can of worms and announced this occultation on our Unistellar web site in the hope that it would motivate our citizen scientists to observe the object.

A journalist heard about this prediction and, as a seasoned reporter, challenged its accuracy. Fortunately, he contacted an IOTA group that ran its own calculation and confirmed that indeed these occultations were going to happen. That’s the way science works, and I am glad our prediction was confirmed by an independent party.

Unfortunately, the weather gods were not with us on February 22nd. The entire observing area was cloudy or rainy. One Unistellar citizen scientist, Karen Flair, attempted to observe Apophis in Park City, UT, but without success because of the clouds.

Because we knew that the eVscope could observe this occultation, and because interest in the event was growing among amateur and professional astronomers, we decided to redouble our efforts and try again on March 6th with what we called a “private citizen science event.”

The first step in our plan was to identify the best place to observe the event, which meant estimating the odds of having clear weather, a significant number of citizen science astronomers nearby to help out, and accessibility during the current pandemic. I decided to focus on the beautiful state of Colorado, since it’s home to about fifty potential astronomers and is relatively easy to get to from San Francisco, where I live. On March 2nd, I sent our fifty potential citizen astronomers a note explaining them the importance of this event, the difficulty of the observation, and how their contribution could help “save the world” (or at least help humanity to sleep better) by nailing down the orbit of the “God of Chaos” asteroid. To my astonishment, I received a dozen replies expressing interest in participating.

In the meantime, the NASA-JPL team attempted to observe Apophis using the Goldstone radar antenna, and, after combining data generated during multiple nights of observing, managed to obtain an echo that allowed us to refine the orbit of Apophis. Josselin refined the path based on this new information, which shifted the asteroid’s trajectory by 1 km to the south, with an uncertainty of 1.5km on the surface of the Earth.

Even though the eVscope is easy to use, observing occultations is complex and challenging because this is not a familiar mode for most observers, and the work has to be done under strict time constraints. This occultation, for example, was expected to last for a mere 30-100ms and data recording had to start at precisely 11 p.m. MST. To help prepare for these difficulties, we had an online session with our volunteers on Friday, March 5th, which I conducted from my home in San Francisco. I showed them how to observe and discussed the time restrictions and the process. Everybody seemed ready to go, so the only uncertainty was the weather forecast which, unfortunately, seemed highly unsettled.

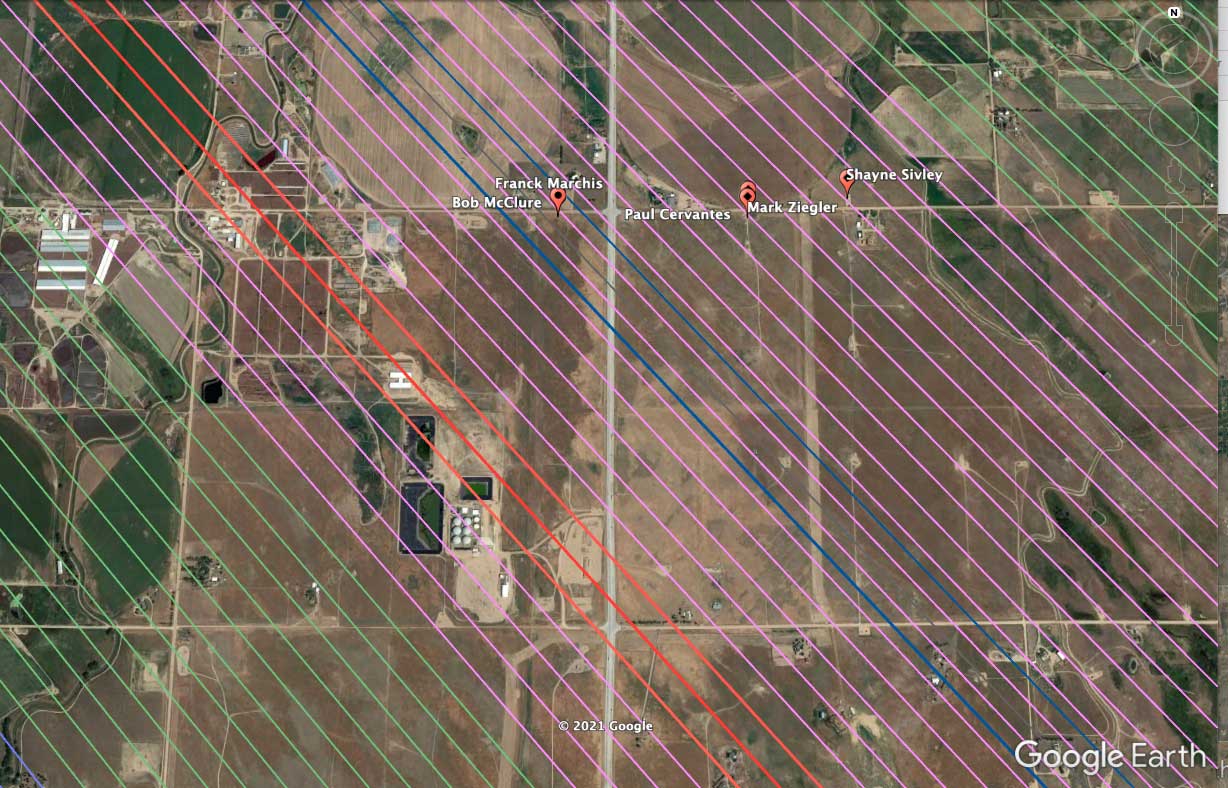

After landing in Denver on March 6th, I was greeted by a clear skies and bright snowy mountains. So, I did not regret heading to Colorado (sorry Dallas, our second choice). While I was in the air, the IOTA group had organized its campaign with stations in Louisiana. David Dunham was sending us regular reports on the work being done there. The weather was nice in Louisiana, where veteran amateur astronomers had about thirty telescopes. Marc Buie, an astronomer at Southwest Research Institute (SWRI), was also involved in the campaign, and sent his prediction about the occultation’ path, which was very close to ours. Our strategy was to maximize the chance of detecting the event by locating our bases across a 6-km band separated by 200 m. The path of centrality was divided into bands numbered from A1 to A72, with A36 at its center. I sent our astronomers an email letting them know about our plans, but ultimately knew that the weather would determine where we located our Unistellar stations.

At 9:30 p.m., seven of us met at Colorado Mountain Skydive, a small airport located south of Greeley. This was the first time we had met in person but there was no time for collegial conversation. The sky was clear just above us, even though clouds loomed all around. Unlike February 22nd, the gods of weather were with us this time.

We confirmed that everybody knew how to use their scopes and turned the hood of one of our cars into a desk on which we discussed the location of our stations and the locations of the other astronomers planning to observe the occultation. We chose Road 46 as the place on which to distribute our stations. At 10 p.m., we left in pairs to set up our stations in preparation for the event:

- Shayne Sivley and his wife headed to A45

- Mark Ziegler and Paul Cervantes (with his dog Riley) headed to A42

- Bob McClure, Jonathan Horst, and I were on A37

Bob, Jonathan, and I found a nice spot near the target location and were careful to position ourselves far away from potential car headlights, even though the road seemed deserted at this late hour. We set up two eVscopes near each other, and were getting ready to start our work when suddenly a group of cars with bright headlights bore down on us. I immediately thought that those must be police cars, since in the past I have had several encounters with officers while observing. Bob volunteered to go talk to them while I finished up the set up. From where I was standing, I could hear part of the conversation he was having with the police. Apparently, someone reported us , as two cars parked on the side of the road with people walking with two large pack backs —the ones holding our eVscopes— were considered suspicious activity. The officers checked Bob’s ID as he explained what we were doing and why it was important. After a cordial but tense exchange, Bob told them that he had to leave because “we may be saving the world” and 10 min before the event was set to begin, they finally let us see the stars again.

All stations were in place and ready, including distant ones:

- Bob MacArthur and his son (A36, 17 km from us)

- John and Ellie Visser (A47, 40 km from us)

- Charlie and Christina Bicknell (A35, 50 km from us)

- Ryan and Sharon Tirashi (A36, 80 km from us )

At 11 pm MST, we almost simultaneously recorded observations of the event and waited quietly for two minutes. It was so quiet I could tell that some of us held our breath.

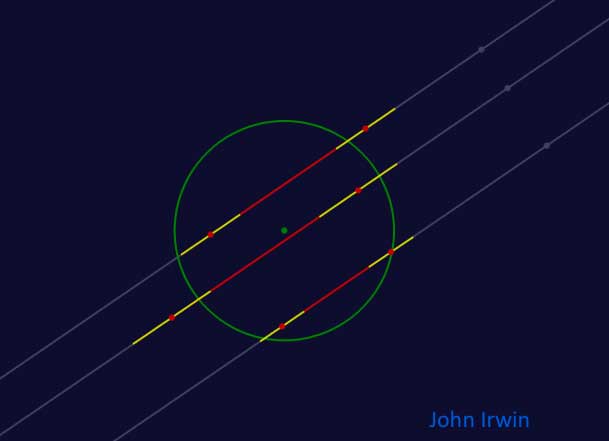

Distribution of the Unistellar observers along the path of the occultation. The red line indicates the location of the detected shadow. We were very close (~650 m).

As the adrenaline worn off while driving back, we realized that we had succeeded in recording an historic event. We had no idea whether we got the shadow of Apophis on Earth, but we knew that our efforts were not in vain.

Fast forward to my return to California. While the Unistellar team was processing the data on Monday, March 8th, we got the first report from other observers. Three of them, in Oakdale, LA, did indeed detect the event! These were located near the lines A28, A29, A30, and therefore only 700 m from our stations. In their observation, David Dunham and Richard Nugent saw the star disappear for of 0.1s, roughly half the time it takes to blink an eye.

We are still analyzing all of the data but we can already report some interesting findings. First, the event seems to have lasted longer (some predicted only 0.035 ms) than expected. It’s possible that the asteroid’s shape and the pole solution we used to make this timing prediction was in fact inaccurate—or, maybe, Apophis is bigger than expected. Second, we have now an extremely accurate position for this asteroid, which will allow us to refine its orbit. NASA-JPL has already calculated a new orbit and will use this data to predict the track for another occultation that is to happen in Europe on March 11, 2021 (yes, soon!). The error on the track is only a few tens of meters based on Paolo Tanga’s prediction. Now we can mobilize our European colleagues to confirm this result and eventually derive an even better estimate of the shape and size of Apophis!

I will end here by saying that the March 7th occultation was an extraordinary achievement. It shows us at our best, when scientists across the world collaborate to make predictions, and citizen astronomers and amateur astronomers work together to coordinate their efforts and succeed. True, I would have loved it if the Unistellar network had detected this occultation with one of our mighty eVscopes, but ultimately what matters is that we predicted this event and we contributed to this campaign with our time and resources.

On the top of that, this event allowed me to connect with new people who share an interest in astronomy and will probably attempt to observe another occultation or participate in some other scientific event that is visible in the beautiful skies above Colorado. I am grateful for this encounter and for the wonderful stories we can now share with our friends and family; stories of the universe that make us who we are: humans under the same stars.

Clear skies

Franck M.

Thanks to all our citizen astronomers, IOTA group, and the Unistellar team.