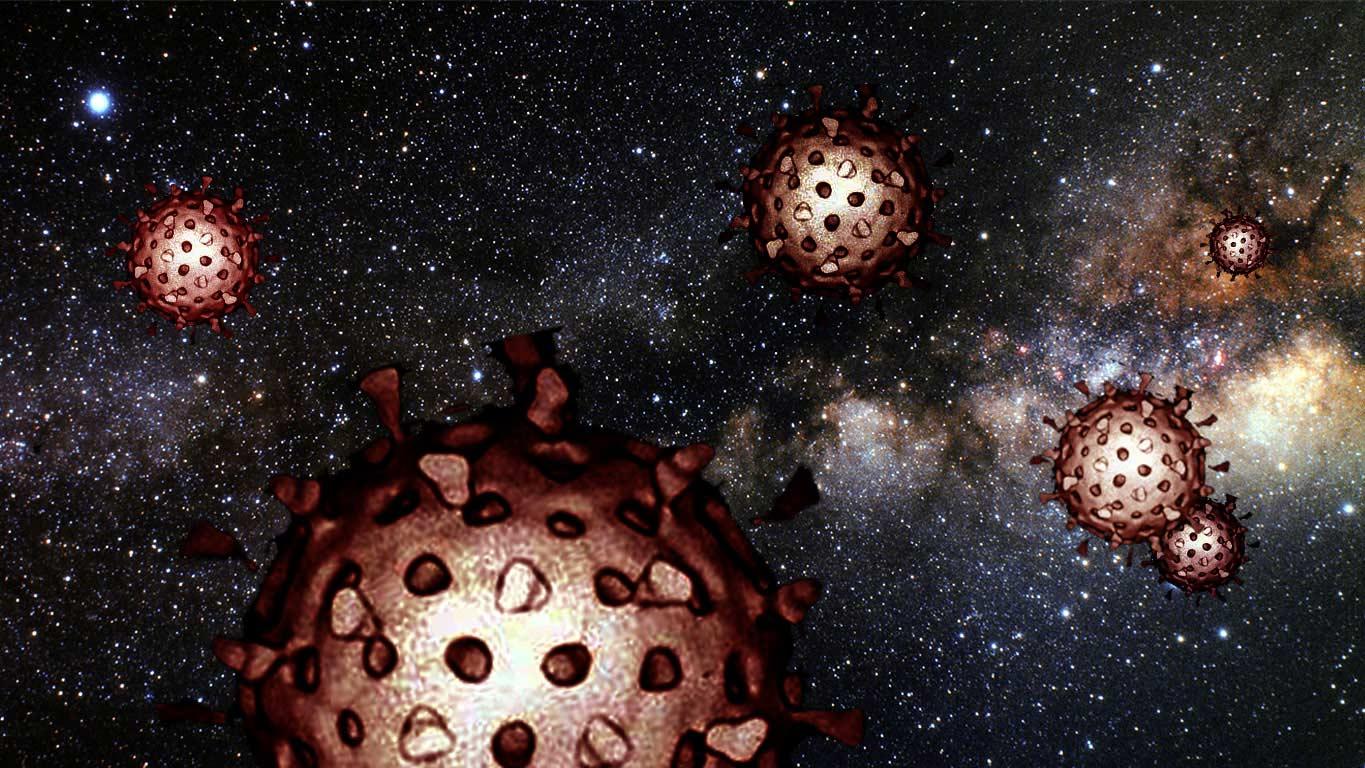

President Trump has called it a “foreign virus,” but could the pandemic now sweeping the globe be considerably more foreign than the U.S. president believes? Some academics have argued that such plagues could be interlopers from space.

Every day, about 100 tons of cosmic dust rain onto Earth, swept up as our world hurries around the Sun. The dust mostly consists of very small, unseen particles, although anything as big as a sand grain can stand out as a shooting star when it self-immolates in the upper atmosphere.

A small group of scientists at the University of Cardiff has long maintained that at least some part of this relentless dust storm is not simply inorganic material from broken-up comets, or bits of rock kicked off planets in other star systems. It also contains microbes that can, and do, cause disease here on Earth.

The academics insist this is a serious idea, the brainchild of some smart people. Panspermia, life that spreads through space, was most famously championed nearly a half-century ago by celebrated Cambridge cosmologist Fred Hoyle. Since Hoyle’s death, the idea of an extraterrestrial vector for terrestrial pathologies has continued to be promoted by Chandra Wickramasinghe, a former colleague of Hoyle’s and an astrobiologist who’s now at the University of Buckingham. In 2003, Wickramasinghe and coworkers published a paper in The Lancet, the prestigious British medical journal, suggesting that the SARS virus could hail from beyond our planet.

This may sound like a story line from “The Twilight Zone,” but the premise, at least, is defensible. Disintegrating comets and colliding asteroids spread bits of material throughout our solar system. Some particles can come from farther afield. When large meteors slam into a planet, the high-velocity impact launches a cloud of debris. Most of that quickly falls back to the ground, but some may be lofted upwards at a speed sufficient to cause it to escape into space. There it will wander forever, unless – by accident – it collides with another object.

The panspermia proponents argue that this thin fog of material is not entirely benign. It not only brought SARS to Earth, but also mad cow disease and the 1918 flu.

The exotic appeal of this idea – a real-life incarnation of Michael Crichton’s “Andromeda Strain” – butts up against the less sensational take of most biologists. The latter believe that the Cardiff scientists are simply mistaking terrestrial activity for extraterrestrial activity. In 2017, a Russian cosmonaut claimed there were other-worldly microbes on the International Space Station. The cosmonaut said that swabbing the ISS produced bacteria that were not present prior to launch. If true, this would be real evidence for panspermia. But the claim weakened when experts pointed out that plenty of earthly bacteria would have been unavoidably sent into space when the ISS hardware was lofted skyword. They say the cosmonaut had simply swabbed up terrestrial contamination.

Dubious claims aside, there’s also a fundamental problem with the idea of sickness from space. Pathogenic microbes and viruses are dependent on an intimate “understanding” of the biology they disrupt. The game plan of viruses is to commandeer cellular machinery to make copies of themselves. They are exquisitely attuned to the specific chemistry of earthly life, itself the result of billions of years of evolution. To think that organisms from other worlds – worlds where DNA might not even exist – would be capable of successfully manipulating our cells is like assuming that your house key would unlock a random door in Tibet.

It’s jarring to think that millions of people can be laid low by bits of biology that don’t hail from Earth. But it’s an idea with a low probability of being correct. As scary as it may be, the coronavirus is not likely to be a space invader. It’s a fellow Earthling.