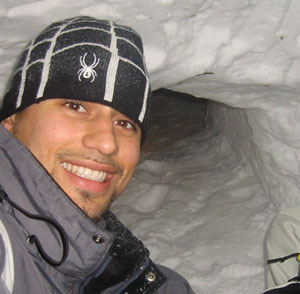

Franck Marchis joined the SETI Institute as a Principal Investigator (PI) or lead scientist in 2007. He is also an assistant research Astronomer at the University of California Berkeley. Franck received his Ph.D. in 2000 from the University of Toulouse, France, in planetary science. His studies and research have taken him throughout the world, and he now dedicates most of his research to monitoring Io's volcanism and the study of multiple asteroid systems using the Keck-10m telescope and the support of CfAO, an NSF science and technology center and NASA planetary astronomy program. Io is the innermost of the four Galilean moons of the planet Jupiter. With over 200 active volcanoes, Io is the most geologically active object in the Solar System. You can learn more about Franck and his research in his contributions to the blog, The Cosmic Diary. .

Franck, please describe your research and the opportunity that now presents itself.

I’m primarily using ground-based telescopes to observe bodies, essentially asteroids, moving through our Solar System. I’m looking for multiple asteroid systems, which are asteroids with moons or pairs of asteroids orbiting around their center of mass. I also monitor the volcanic activity on Io, a satellite of Jupiter.

This research is particularly exciting right now because we’ve finally overcome the limit of atmospheric turbulence. When you observe using a ground-based telescope, Earth’s atmosphere blurs the image. Thanks to scientific advancements, called adaptive optics systems, we can now overcome this limitation. With these systems, we can basically achieve the same quality as if we were observing using an 8-10 meter class telescope situated in space. This technology enables us to monitor the volcanic activity of Io and see moons around asteroids. Twenty years ago, this was not possible.

What is the coolest thing about your work?

What I find most exhilarating when observing is the very real possibility that I will discover something previously unseen or undocumented. Also, ground-based telescopes provide instant gratification, unlike a space mission in which you may have to wait years for the results. On more than one occasion, I’ve been with a few colleagues or alone on my telescope and discovered a new object or witnessed an unexpected phenomenon. For instance, last August, we discovered two moons around Minerva, an asteroid in the Main Belt. Sometimes we get to see a gigantic eruption on Io like the one we witnessed in February 2001 at Keck Observatory. On other occasions, I’ve written proposals to tackle a very difficult observation, such as observing Jupiter’s atmosphere using two Galilean satellites (these three bodies are moving with respect to each other) with a new type of adaptive optics system, and we’ve achieved success! There are so many stars and asteroids -- you can basically create your own job and your own niche project. To me, astronomy is like the poetry of science.

What I find most exhilarating when observing is the very real possibility that I will discover something previously unseen or undocumented. Also, ground-based telescopes provide instant gratification, unlike a space mission in which you may have to wait years for the results. On more than one occasion, I’ve been with a few colleagues or alone on my telescope and discovered a new object or witnessed an unexpected phenomenon. For instance, last August, we discovered two moons around Minerva, an asteroid in the Main Belt. Sometimes we get to see a gigantic eruption on Io like the one we witnessed in February 2001 at Keck Observatory. On other occasions, I’ve written proposals to tackle a very difficult observation, such as observing Jupiter’s atmosphere using two Galilean satellites (these three bodies are moving with respect to each other) with a new type of adaptive optics system, and we’ve achieved success! There are so many stars and asteroids -- you can basically create your own job and your own niche project. To me, astronomy is like the poetry of science.

I also get to conduct my research in some of the most beautiful areas in the world. Ground-based telescopes are located in Chile, Hawaii, the Canary Islands, Europe, and California. The ones I use most often are Keck in Hawaii and Lick Observatory in San Jose, California. You can’t beat the views!

Why should the public care about your research?

When we discover moons around asteroids, we can get an idea of the collisional history of our Solar System by determining how the planets were formed. We can also derive information about the composition of the asteroid. This has a direct impact on the search for natural resources, such as understanding where we may find water and what the mineral content is in asteroids. Since we know asteroids are the bricks which form the planets, their composition and internal structure have direct relevance to the origins of planets, including Earth.

What do you currently consider your biggest challenges?

Funding is the biggest challenge right now. I sometimes have to write five to seven grant proposals per year. I first have to find a project idea, and then I need to write the grant, create a group, justify everything requested in the grant, while all the time realizing that there is a strong likelihood the research proposal will not come to fruition. I estimate only 10 percent of grants get funded. Additional difficulties when using ground-based telescopes is we also have to write and win grant proposals just to get telescope time. So I need to write twice as many proposals as those who work on space missions and significantly more than the theorists.

How did you come to join the SETI Institute?

When I was at UC Berkeley, I felt I had hit the so-called “glass-ceiling,” with little potential for growth. A colleague suggested I consider working at the SETI Institute. I thought the Institute was only involved with the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. I checked it out and it wasn’t at all what I expected. I was really pleased to learn of the diversity of scientific disciplines as well as the phenomenal talent working in the Carl Sagan Center of the SETI Institute. The Institute has a large community of planetary scientists with whom I’ve started collaborating on several projects. I’ve learned a lot since I arrived here.

What first sparked your interest in science?

I’ve always been interested in science. As a boy, my father told me interesting facts about science, space, and how to solve simple equations. I enjoyed biology in particular. In college, I focused on math since I hadn’t decided on a career path. I steered into space science when finishing my Bachelor’s degree in mathematics. I realized astronomy would give me the freedom to experiment in new areas and allow me to travel, which I love, and learn several new languages, which was a goal of mine.

What motivates you?

I like the possibility that something unexpected is going to happen. I also enjoy the sometimes hectic pace, with adrenaline pushing me to work like crazy for two days straight to meet a looming deadline. Additionally, I like the fact that I’m publishing papers and working with students. I don’t see myself locked away in a solitary lab. I find human interaction important and motivating.

I often have the opportunity to talk with students who would like to work at the Institute and I listen to their reasons why and enjoy their excitement at the prospect. I especially appreciate meeting with students from a minority population, which I believe is very important to take into consideration. Being of French, Malagasy, and Indian descent, I would love to see an increase in the number of different ethnicities working within science.

What was your dream job as a child?

I always saw myself as a scientist or university professor. At UC Berkeley, I taught "Introduction to Planetary Science" three times and loved it! As a young man, I also had a moment when I wanted to be an astronaut but when I learned more about that career, I didn’t think it would be as interesting as becoming a scientist.

Who do you admire most and why?

I admire people like Gandhi, who have a very strong philosophy of life and apply it at all times. I’m inspired by people who really want to change the world and have an idea how to do it – this is very important to me.

What is your philosophy of life?

Don’t do it if you don’t like it. There will always be bad moments, and if you don’t like what you’re doing, you will just drop.

How do you spend your free time?

We have two young children, so I spend my time with my family. My kids are at the age where everything is magical and fun, which is cool because I forgot how that was. When we do things together, whether it’s taking a trip, seeing trains, or going to a museum or park, I’m constantly reminded of how magical and fun the simplest of activities can be.