While today marks the end of Kepler’s data collection, it marks the beginning of a new era in scientific exploration.

Fifty-seven years ago, in 1961, a small conference of astronomers sat down and hashed out what we would need to know to determine how many civilizations there could be in our galaxy presently capable of communicating with us. The resulting equation, named after the conference organizer and SETI pioneer, Frank Drake, has just seven terms:

- How often do stars form?

- How many of those stars have planets?

- How many of those planets could be suitable for life?

- How often does life arise when the conditions allow?

- How often does live evolve into intelligent beings?

- How often do those beings develop technology to enable interstellar communication?

- And how long do those civilizations emit signals that are detectable in space?

These seven big questions in this simple little equation, known as the Drake Equation, proved to be an enormous scientific challenge to answer, and prior to the launch of the Kepler Mission in 2009 we really only knew the answer to the first.

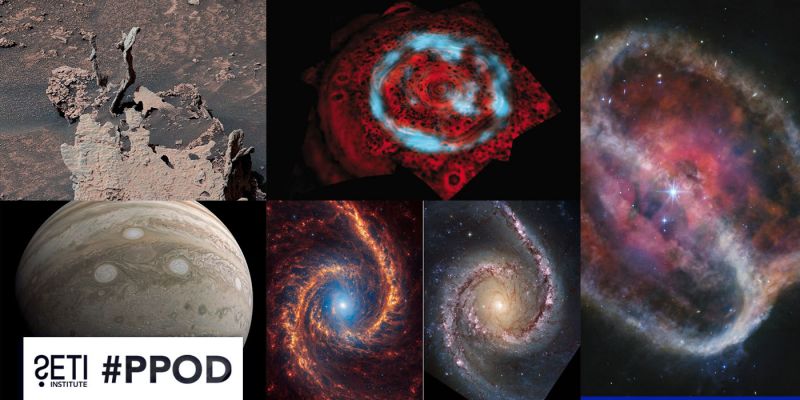

Kepler was NASA’s first mission dedicated to the search for planets around other stars, called exoplanets. The first exoplanet was only discovered 20 years prior to launch, and just a few hundred more were discovered in that time, with most of them inhabitable and more similar to gas giants like Jupiter than Earth. In the nearly ten years since Kepler’s launch, data from the spacecraft has resulted in the detection of thousands of exoplanets, with a multitude of them the size of Earth or smaller, and many of them at the right distance from their star to possibly support life as we know it. Thanks to data from Kepler we now have answers to two terms of the Drake equation that had eluded us for fifty-seven years --- we now know there are even more planets than stars in our Galaxy and a significant number of them could have the right conditions to be habitable.

We’ve also discovered exoplanets and systems of exoplanets that are wilder than the imagination of most science fiction writers. Along with data from Kepler’s extended mission, K2, we’ve experienced leaps forward in our understanding of physics at the centers of galaxies, exploding stars, star formation and evolution, and even the properties of asteroids and planets in our own solar system.

And the fun has just begun. Data from Kepler and K2 is so vast that it will continue to be mined for decades. New NASA missions like TESS, James Webb, and WFIRST will continue to find even larger amounts of exoplanets and sniff out what their atmospheres are made of. Data from spacecraft launched by our scientific siblings in the European Space Agency are complementing data and enhancing discoveries from Kepler, as well as making novel discoveries of their own.

While today marks the end of Kepler’s data collection, it marks the beginning of a new era in scientific exploration. We now know that Earth is not alone. The odds of humanity not being alone in the cosmos look high. But there are still a lot of big terms in that simple little equation to figure out. The search continues!

You can learn more about Kepler here.