It’s probably safe to say that the biggest astronomy story of the past two decades is that the universe is studded with planets. Sweden’s Nobel Prize committee clearly agrees, as they just handed their coveted physics award to Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz – the two Swiss astronomers who were the first to find convincing evidence for a world around another normal star. What they uncovered was a bulky planet orbiting 51 Pegasi – an otherwise-unremarkable Sun-like star about 50 light-years away.

Since that 1995 discovery, nearly four thousand additional exoplanets have been uncovered. That’s an impressive number, so it’s fair to ask whether this new knowledge has changed the way we look for E.T.

First, note that few of these exoplanets are the kind you’d expect would cook up intelligent extraterrestrials. The universe boasts many, many second-string exoplanets: large water-logged worlds, vaporous gas balls, or objects that are simply too hot or cold to be great places for biology. Nevertheless, preliminary estimates suggest that about one in five star systems contains a planet something like the Earth. That adds up to tens of billions in our own galaxy, and that doesn’t count all the moons that might also incubate life.

So, given all this newly uncovered real estate, shouldn’t SETI (the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) scientists be assiduously aiming their antennas its way? Wouldn’t doing so better the odds that we’ll trip upon some alien BFF?

Well yes. And indeed, many of these exoplanet systems have been surveilled by SETI. But the real influence of exoplanets on the hunt for E.T. is more subtle.

To understand why, let’s briefly return to those golden days of yesteryear. When large-scale signal searches first got underway in the early 1990s, we simply didn’t know which stars had planets. In fact, it was conceivable (but a poor bet) that none of them did. So the SETI scientists preferentially pointed their instruments in the directions of Sun-like stellar systems. After all, the Sun was the only star we knew that (jokes aside) shone on intelligent beings.

Clearly, this was a conservative strategy, and hard to fault – somewhat like restricting your dining choices to well-known restaurant chains. Doing so confers a reasonable expectation of getting an edible meal, despite the fact that better fare might be had elsewhere.

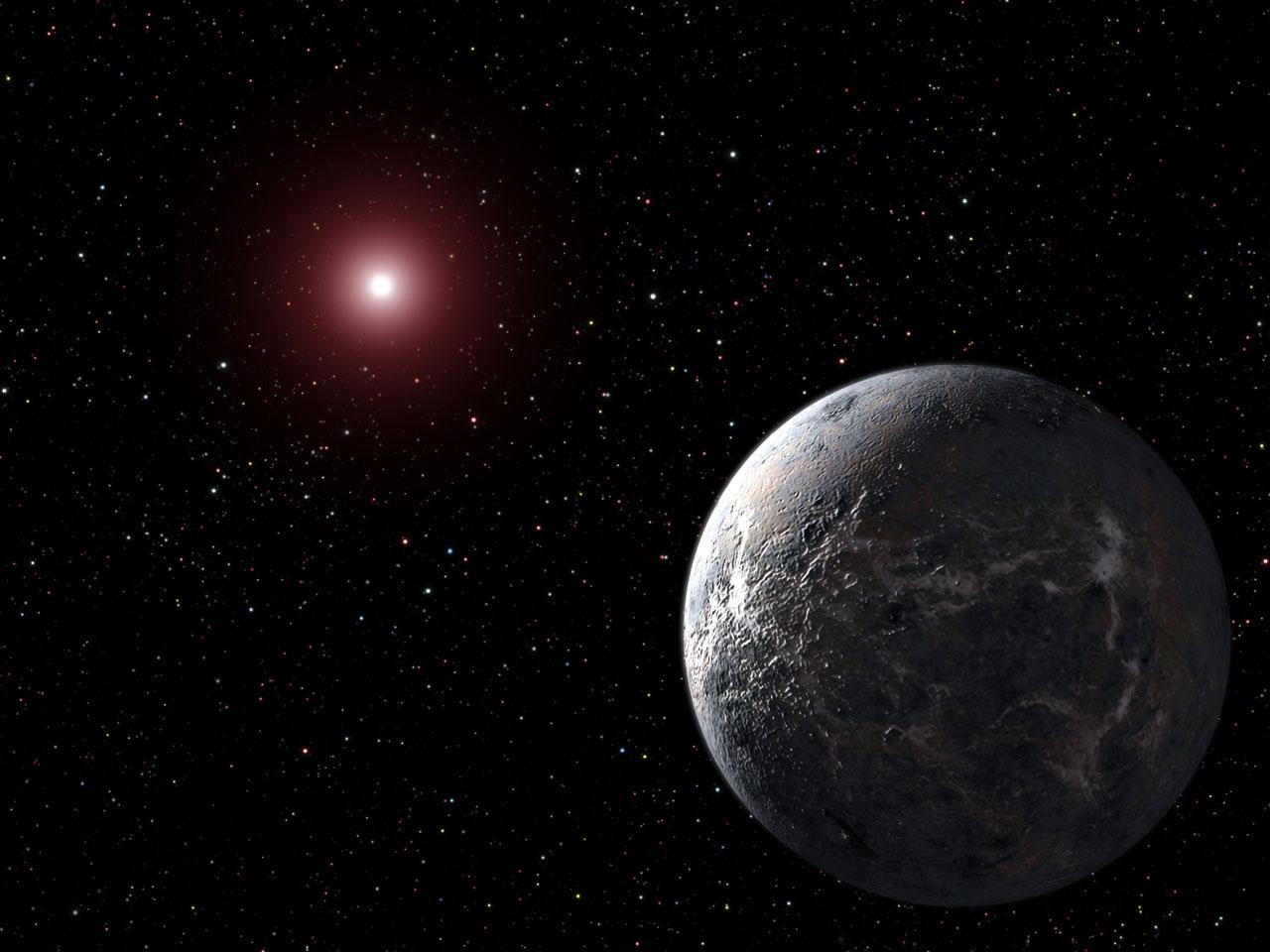

The exoplanet discoveries have expanded the choices for researchers, as well as reduced their personal anxieties because they finally can be certain that planets are plentiful. As an example, there’s a type of star that scientists had always excluded from the SETI club – namely red dwarfs. These bantam stars were considered unlikely to host many close-in planets – worlds that orbited near enough to receive adequate starlight for sustaining life.

But the exoplanet hunters have proven that assumption wrong. Several red dwarf stars have been found that are ringed by possibly habitable planets. And since 75 percent of all stars happen to be red dwarfs (while only 8 percent are similar to the Sun), this is like suddenly learning that there are ten times as many restaurants in your neighborhood as you once thought. Your drive to dinner is shortened, and your menu options are increased.

So, the practical result of finding lots of planets has been to shift SETI strategy from looking at a certain type of star system to simply looking at all the nearest ones. Indeed, on average the systems examined today are only half as far away as when only Sun-like stars were examined. Any signals would be four times stronger and, of course, if we find someone at home, a back-and-forth conversation might be more practical.

Nobel Prize winners Mayor and Queloz weren’t looking for planets when they found one around 51 Peg, but they are being be justly credited with paying attention to their data and realizing what it implied. Like many discoveries in science, their discovery was accidental, but their realization of its importance was not.