The Jupiter-bound mission seeks to discover if the icy moon contains the ingredients necessary to support life.

In the search for life beyond Earth, scientists have traveled to distant locations — Antarctica and its ice sheets, Chile and its high desert lakes, and even snow-capped mountain peaks. And in every single place, we have found life. So, what could we find elsewhere in our solar system with similar conditions? NASA’s Europa Clipper Mission will soon seek an answer to that question by studying the icy satellite of Jupiter, although the spacecraft will not arrive until 2030. Meanwhile, scientists, journalists, and streamers congregated in Florida, excited for the October launch of the mission atop a Falcon Heavy rocket. On 14 October at 12:06 p.m. EDT, the spacecraft lifted off from Kennedy Space Center and successfully deployed the enormous solar arrays that power the mission.

Before anyone sets their expectations too high, Europa Clipper is not on a mission to find life but to determine how habitable the subsurface ocean may be. So, how do we know there’s a subsurface ocean?

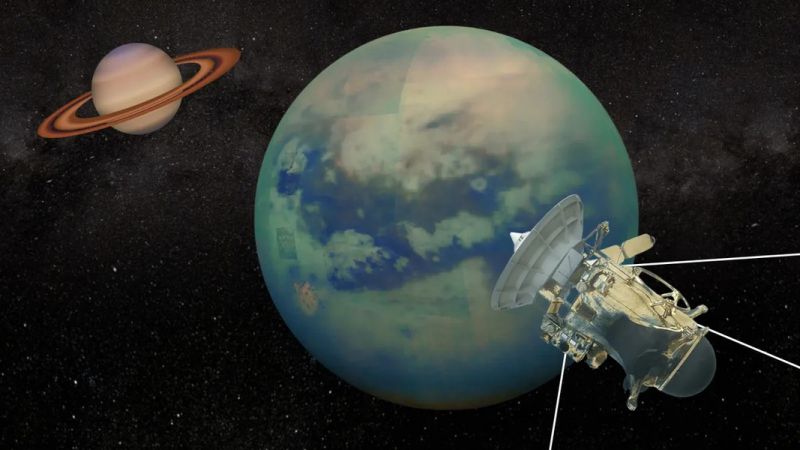

From data collected by ground-based telescopes and previous missions, including NASA’s Galileo and Voyager, scientists discovered that Europa’s surface was composed of water ice, with very few craters. Few craters in solar system terms usually mean a young surface, so the water ice is being replenished somehow. That discovery led to an understanding that the resonant orbits of the Galilean moons cause regular gravitational pulls against Jupiter’s gravity, causing the moon interiors to heat up. Volcanic eruptions on Io were predicted from this hypothesis and eventually observed with Voyager 1 in 1979.

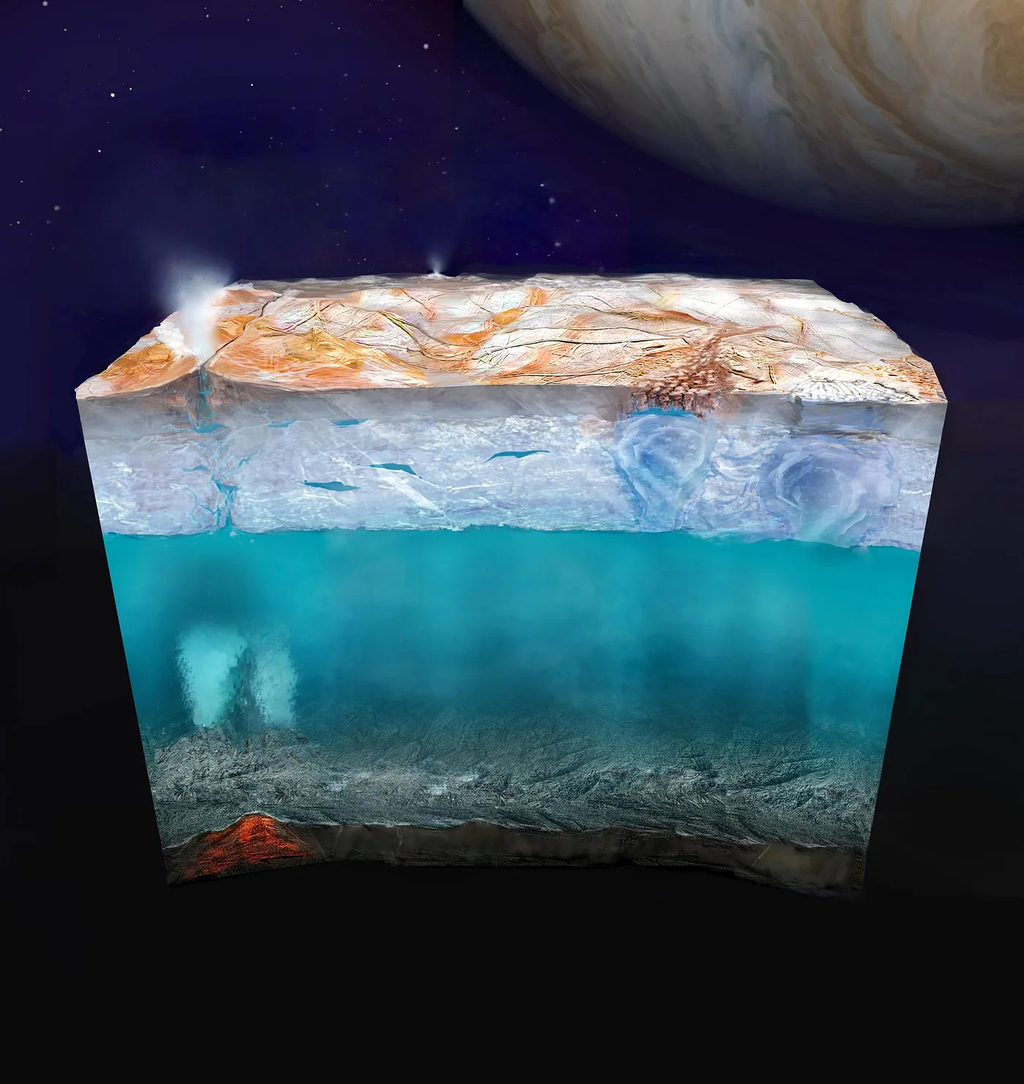

However, the evidence predicted a subsurface ocean under a thick icy shell for Europa rather than volcanism. The moons’ and Jupiter’s push and pull causes tidal heating that keeps the ocean liquid and could even cause hydrothermal venting on the ocean floor. Here on Earth, hydrothermal vents are prime locations for a wide variety of life forms that live off the nutrient-rich eruptions. As Project Staff Scientist Cynthia Phillips explains, “Europa’s surface is covered with ice, but under that ice, there’s this giant ocean of liquid water. We think there’s actually more water there than all of Earth’s oceans combined. That ocean could be a great place to look for life.”

If we’re not searching for life, what are we looking for? The Europa Clipper mission has three main science goals:

- Determine the thickness of Europa’s icy shell and how the ocean interacts with the surface.

- Investigate Europa’s composition and its ocean to determine if it has the ingredients to permit and sustain life.

- Characterize the geology of Europa.

Goal number two is closest to the heart of the SETI Institute’s mission — determining whether the icy moon and its subsurface ocean are habitable and capable of supporting biology. As we understand it, life’s ingredients include water, organics, energy, and stability. The spacecraft carries nine science instruments onboard to find out what is available.

From NASA’s website: “The spacecraft’s payload will include cameras and spectrometers to produce high-resolution images and composition maps of Europa’s surface and thin atmosphere, an ice-penetrating radar to search for subsurface water, and a magnetometer and gravity measurements to unlock clues about its ocean and deep interior. The spacecraft will also carry a thermal instrument to pinpoint locations of warmer ice and perhaps recent eruptions of water, and instruments to measure the composition of tiny particles in the moon’s thin atmosphere and surrounding space environment.”

Europa Clipper will make about 50 close flybys to gather data, dipping as low as 25 kilometers above the icy surface. Each pass will cover a different location, giving scientists a nearly complete view of the moon. That data will take years to analyze fully, but scientists are hopeful and excited about the future.

This article was originally published on medium.com.