Hoping to unravel some of the mysteries of Mars and the Moon, SETI Institute Senior Research Scientist Janice Bishop and Dr. Merve Yeşilbaş traveled to the frosty Cold Surfaces Spectroscopy Facility at the University of Grenoble in France. Bishop and Yeşilbaş's partnership is rooted in space exploration. Yeşilbaş, once a postdoctoral researcher at the SETI Institute, continues to join forces with Bishop on various projects.

Funded by the Europlanet Society, Bishop and Yeşilbaş wanted to measure the spectra of various minerals and analogs under vacuum conditions at a super cold 193 K to investigate changes in the spectra under cold conditions. The facility is a laboratory where reflectance spectra dance under vacuum and sub-zero conditions, revealing the secrets of extraterrestrial analog materials spanning from 0.35 to 4.8 µm (microns). It's a place where science fiction meets reality.

"These types of measurements are essential for remote sensing on the Moon and Mars where temperatures are often much lower than Earth," said Bishop.

Bishop and Yeşilbaş exposed a variety of minerals to vacuum conditions as cold as 193 K – that's -80.15°C for the Earthlings among us. Why? Because the Moon and Mars can get pretty chilly, understanding how spectral features shift in the cold is crucial for remote sensing. The team unearthed significant shifts in the spectra of sulfate and iron oxide minerals, promising better characterization of minerals on the Red Planet.

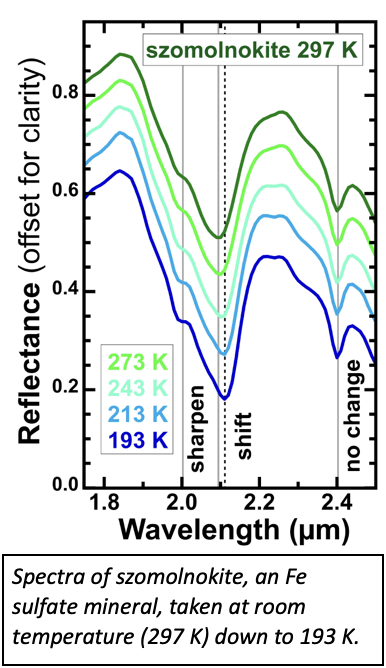

A specific example of the spectral changes they observed with decreasing temperature is shown here for spectra of szomolnokite, an iron sulfate mineral. The band near 2.0 µm sharpened as we lowered the temperature, the band near 2.1 µm shifted towards longer wavelengths, and the band near 2.4 µm did not change.

The scientists also explored lunar analogs. Due to water or hydroxyl, silicate minerals and lunar stand-ins often display a distinctive band near 3 µm. "We were curious if this feature would change under vacuum or low-temperature conditions, and we're in the process of analyzing the data to characterize these changes," said Yeşilbaş.

Behind the scenes, the Europlanet Society and team at the Institute for Planetology and Astrophysics at the University of Grenoble, including Bernard Schmitt and Olivier Poch, helped make this work possible.